Gianluca Boccia

|

| Members of the Provisional IRA's leadership. From left to right: Martin McGuinness, David O'Connell, Seán MacStíofáin, Seamus Twomey. Source: Wales Online. |

Introduction

I cannot help but frown whenever I come across articles that bitterly criticise the ‘IRA’. I do not take issue with the commentary itself, so long as it is balanced and supported by evidence: I, for one, firmly believe that historical figures and events should always be subject to careful scrutiny. In the pursuit of truth, he who claims to be a history enthusiast must be willing to question his beliefs. I do, however, object to the improper usage of the term ‘IRA’, which is commonly associated with the Provisional IRA's terror campaign during the Troubles (1969-1998). The inevitable consequence of this flawed narrative is the widespread myth that Irish Republicanism is rooted in sectarianism and incapable of achieving its goals without relying upon terrorism.

It cannot be denied that the Provisional IRA itself is largely to blame for this distorted perception: according to Vincent Byrne, a veteran of the Anglo-Irish War (1919-1921) who served with the Squad, the Provisionals ‘destroyed the name of the IRA’. [1] General Tom Barry, a Republican legend, disavowed the PIRA with equally disillusioned terms, stating that ‘the men who were carrying out the recent killings (...) could not be called IRA’. [2] The fact that Pro-Treaty and Anti-Treaty elements of the old guard alike distanced themselves from the Provisional movement indicates that the group's tactics - not its objectives, some of which may be considered noble - were the alienating factor. Indeed, Barry was appalled by the 1974 Birmingham bombings, which killed twenty-one innocent civilians. The General was not opposed to the armed struggle per se; but he could not bring himself to condone such a barbaric attack on ‘obvious civilian targets’. [3]

‘The Good Old IRA’ and the Troubles

‘Overall, ‘The Good Old IRA’ makes for a thought-provoking read and exposes the brutality of a war that is often romanticised, but fails to draw other parallels between the two periods.’

|

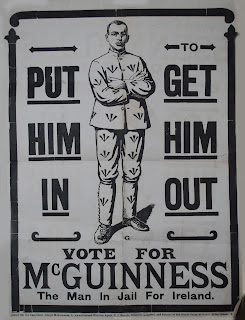

| Joseph McGuinness' 1917 election poster. Source: The Irish Story. |

Michael Noonan, the Irish Minister for Justice, echoed Barry's sentiment during a commemorative speech at Béal na Bláth in 1984. His condemnation of the Provisional IRA's ongoing campaign outraged Sinn Féin, then the group's political wing, sparking a decades-long debate. Danny Morrison, the party's publicity director, penned a short pamphlet so as to expose this permeating hypocrisy. ‘The Good Old IRA’, his biting riposte to Noonan's remarks, purports to be a partial collection of the army's worst atrocities and is mainly comprised of contemporary newspaper clippings, which the author provocatively takes at face value. As Niall Meehan pointed out, by sourcing information from the Redmondite Irish News, an anti-Sinn Féin publication, Morrison succeeded in exposing a bias in favour of the status-quo. [4] ‘The Good Old IRA’, then, does not seek to provide nuanced accounts of the appalling events it includes; it merely attempts to shock the readers, forcing them to come to terms with the brutality of the War of Independence. The limitations of this approach are rather evident.

|

| Seán Treacy. Source: RTÉ |

The lopsided pamphlet includes a tongue-in-cheek preamble written by Mick Timothy. After a lengthy tirade against Michael Collins (which contains minor historical inaccuracies: Collins was never the ‘IRA's leader’ - Mulcahy and Brugha were, respectively, the Chief-of-Staff and the Minister for Defence; this placed them above Collins in the organisation's hierarchy, at least de jure), the pamphlet lists a number of reprehensible, yet not always unwarranted deeds carried out by the Old IRA. While the booklet does offer a glimpse of the Anglo-Irish War's violent nature, it fails to draw other significant parallels between the two periods. Indeed, ‘The Good Old IRA’ is hardly as damning as Sinn Féin's publicity department deemed it to be. Some events herein reported are truly atrocious and unjustifiable: the murder of Mrs. Ellen Morris during a botched raid for weapons is a grim case in point. These actions, which were not sanctioned by GHQ, shed light on the callousness of the most trigger-happy volunteers.

|

| Members of the Irish Republican Army. Source: Roll of Honour. |

More than meets the eye

But ‘The Good Old IRA’, a clever propaganda piece, cannot be considered a scholarly critique of the Irish Republican Army, for Morrison omitted a number of details that would otherwise allow us to properly contextualize several of these incidents. Since this article is not meant to be a thorough analysis of ‘The Good Old IRA’, which I have used as the basis for broader reflections on the IRA, I shall only provide three examples. However, I suspect that a complete dissection of the booklet would bring to light other instances of missing context. The reader ought to decide by himself whether the additional information that I am about to present justifies the IRA's actions.

‘Ex-Brit’? The legitimacy of violence

Henry Timothy Quinlisk, a treacherous informer executed by the Cork IRA, was described by the newspaper as an ‘ex-soldier’. [5] This depiction is misleading at best. Upon his return to Ireland, Quinlisk was actually welcomed by Collins, who provided him with a small amount of money, a new suit and a hotel room. Quinlisk reciprocated this kindness by having the hotel raided. Then, unsatisfied, he colluded with the British Secret Service, hoping to collect the hefty reward for Collins' arrest. Unbeknownst to him, the Big Fellow's network had already infiltrated the British intelligence system, and his treachery was soon uncovered. ‘I have decided to tell you all I know of the organisation [Sinn Féin] and my information would be of use to the authorities. The scoundrel Michael Collins has treated me scurvily (...)’ he wrote, but this letter - now a death warrant - was intercepted by Collins' mole in the Castle. [6]

The booklet quickly glossed over the murder of Alan Bell, who, far from being an ordinary Resident Magistrate, was involved in various intelligence operations (including the efforts to crush the Dáil Loan) and worked in tandem with Inspector Redmond, possibly on the Jameson affair (Jameson, one of Britain's best agents, was later executed by the Squad). [7] This may explain why a loaded revolver was found in one of his pockets. [8]

Oswald Swanzy's role in the cold-blooded execution of Tomás Mac Curtain, the Lord Mayor of Cork, is not explored either. It may be argued - fairly so - that offering insights into these events was not the pamphlet's goal; but such details are essential nonetheless, as they legitimise the IRA's decision to target said individuals.

As stated above, the IRA's worst atrocities were committed in defiance of GHQ. Coogan recalled a dreadful incident that bears an uncanny resemblance to the 1976 Kingsmill Massacre: in reprisal for the murders of three Catholics, three Protestants were singled out and killed in a Belfast cooperage. [9] The North was ravaged by a cycle of tit-for-tat violence, which occasionally spilled over into the Free State, much to the dismay of both leaderships. Tom Hales' order to lay down all weapons and the placement of IRA guards on Protestant premises following the controversial Dunmanway killings (which may not be a clear-cut act of sectarianism*) constituted an unequivocal condemnation of what were perceived as deliberate attacks on innocent civilians. [10] [11] *[12]

The question of legitimacy is particularly relevant. The much-decried slaughter of RIC constables, the ‘fellow countrymen and coreligionists’, was an unavoidable, tragic necessity. The RIC was a paramilitary whose range of action extended far beyond that of an ordinary police force. Its members resided in fortified barracks and were heavily armed. All things considered, there is a strong case to be made that the RIC was a legitimate military target. Interestingly enough, the pamphlet also includes a snippet that denounces the public's tendency to ostracize constables. Albeit cruel, this practice dealt a blow to the enemy's morale and led to mass resignations.

|

| Chief Secretary Hamar Greenwood inspecting RIC constables. Source: RTÉ. |

Dáil Éireann and the IRA

‘Dáil Éireann's seditious nature inevitably brought about the armed confrontation.’

While the Irish did not ‘vote for war’ (has any conflict ever been democratically approved by the people?), Dáil Éireann's seditious nature inevitably brought about the armed confrontation. Indeed, Sinn Féin's Declaration of Independence was a de-facto declaration of war. The document stated: ‘We solemnly declare foreign government in Ireland to be an invasion of our national right which we will never tolerate, and we demand the evacuation of our country by the English Garrison (...)’ (author's italics). [14] In light of this statement, the Dáil could not have maintained a neutral stance on the IRA's activities. Nor can it be argued that the Irish people were unaware of the consequences of Sinn Féin's electoral victory. One of the party's main selling points - aside from abstentionism - was its support of Ireland's POWs. Joseph McGuinness' 1917 election campaign coined the famous slogan: ‘Put him in to get him out.’

After Count Plunkett's election in North Rosscommon, the moderate Irish Parliamentary Party had gone to great lengths to avert another defeat, but to no avail. [15] John Dillon, the IPP's leader, had noticed a sudden shift in public opinion shortly after the executions of the rebellion's leaders. [16] Much to his chagrin, the Volunteers made their reappearance in 1917: De Valera himself was escorted by stewards in uniform during his campaign in Clare, and the words he used to address the crowd were an omen of sorts: ‘To that Government [The 1916 Provisional Government] (...) I offered my allegiance and to its spirit I owe my allegiance still.’ [17]

|

| Éamon de Valera after the Easter Rising. Source: IrishAmerica. |

The IRA's campaign commenced without the Dáil's formal approval; but Brugha's partly successful attempt to introduce an oath of allegiance, as well as de Valera's recognition of the IRA's activities in 1921, highlight a will to form an official bond between Dáil Éireann and its ‘standing army’. [18] [19] Brugha's proposal was met with fierce opposition. Collins was particularly skeptical, and his reservations were shared by numerous commanders and rank-and-file volunteers. The most likely explanation is that Collins and his subordinates feared that Brugha would take over the army. It is no secret that many IRA guerrillas did not think highly of the Minister for Defence, who was, to quote Mulcahy, ‘as brave and as brainless as a bull’. Ernie O'Malley's claim that ‘Cathal Brugha (...) did not know the senior officers well’ might be somewhat of an understatement, given his strained relations with both Collins and Mulcahy. [20]

The Irish Republican Army waged war on the British Empire against a backdrop of civil disobedience. The setting-up of the Dáil Courts was yet another act of sedition that sought to undermine the British administration in Ireland, and the 1920 railway strike is just as worthy of mention.

It cannot be denied that the Dáil's failure to bring the IRA to heel had disastrous effects during the Civil War. However, it must also be noted that de Valera's rejection of the Anglo-Irish Treaty may have swayed a considerable portion of the IRA and nullified Dáil Éireann's efforts to prevent a split. Is it wishful thinking to assume that the moderate elements of the Anti-Treaty faction would not have taken up arms, had the President of the Irish Republic pleaded with them to endorse the Treaty?

|

| A spy label left by the IRA. Source: The Irish Story. |

The IRA, informers and disappearances

One of the most contentious topics is the killing of alleged spies and informers. While Collins' brainchild is rightfully hailed for its pivotal role in the intelligence war, civilian ‘touts’ were executed all over Ireland, with the exception of the following counties: Antrim, Derry, Donegal, Down, Fermanagh, Mayo, Tyrone and Wicklow. [21] In wartime, this practice is commonplace: Resistance movements in WW2 routinely wiped out informers. It has been alleged, however, that the IRA used the intelligence war as a pretext to ethnically cleanse the Protestant minority, in spite of the fact that the overwhelming majority of the civilians executed as spies (142 out of 196) were Catholic. [22] If the percentages of Protestants murdered in each county are to be taken into account, Cork stands out as the only outlier. In his memoirs ‘Guerrilla Days in Ireland’, Tom Barry addressed this issue, claiming that his unit only targeted the Protestants who actively aided the British. [23] Notwithstanding revisionist attempts to depict the IRA as a force driven by sectarianism, Barry's version appears to be correct.

In recent years, the IRA's unusual practice of abducting and disappearing a number of its victims has come under scrutiny. Professor Eunan O'Halpin alleged that some two hundred individuals were done away with in this manner, though his estimates have been rejected by other notable historians, including Borgonovo and Meehan. O'Halpin's claims were explored in the lacklustre "In the Name of the Republic", a two-part documentary series which may have undermined the thesis it sought to present: after a painstaking excavation that bore no fruit, it was discovered that the two presumed victims of the IRA actually survived the conflict. [24] Similarly, a British spy named William Shields evaded capture and managed to escape to the US. [25] Due to the lack of evidence, we may never know the truth about the disappearances. Disappointing as this may be, our thirst for knowledge will not be quenched by dubious claims such as O'Halpin's.

I recommend reading Meehan's ‘Gravely mistaken history’, Borgonovo's ‘Separating fact from folklore’ and Ó Ruairc's ‘Spies and informers beware!’, which delve into this matter with a critical mindset.

Conclusions

Drawing parallels between the Anglo-Irish War and the Troubles is not as straightforward as it might seem: while both periods were dominated by violence, this element alone is not enough. ‘The Good Old IRA’ was circulated to deflect much of the criticism that was being levelled at Sinn Féin for its ties with the Provisional IRA; therefore, the writing of the pamphlet needs to be contextualised. As I have explained, the booklet had strengths and weaknesses: on the one hand, it exposed the brutality of a war that is often romanticised, as well as a tendency to side with the status-quo for expediency; on the other hand, its attempts to compare the IRA to the PIRA were less convincing. Overall, in spite of its shortcomings, ‘The Good Old IRA’ makes for a thought-provoking read.

I shall examine the Provisional IRA and the Official IRA in the second part of this article.

References

[1] Kee, Robert (1980). "Ireland: A Television History", [Film] BBC & RTÉ

[2] McGreevy, Ronan (2020). "Tom Barry said Provos only had ‘themselves to blame’ for losing support", The Irish Times

[6] O'Connor, Frank (1979). "The Big Fellow: Michael Collins and the Irish revolution", pp. 80-84; Coogan, Tim Pat (2015). "Michael Collins: a biography", p. 131

[7] Hittle, Jon Bradley Edward (2011). "Michael Collins and the Anglo-Irish War: Britain's counterinsurgency failure", p. 107

[8] Greene, Patrick O'Sullivan (2020). "Crowdfunding the revolution: the first Dáil Loan and the battle for Irish independence", p. 148

[9] Coogan, Tim Pat (2015). "Michael Collins: a biography", p. 363

[10] Ibid, p. 359

[12] Ibid, see Regan's findings

[15] McGreevy, Ronan (2017). "Put him in to get him out - An Irishman's diary of Joe McGuinness, Sinn Féin and a pivotal byelection victory in 1917", The Irish Times

[16] Coogan, Tim Pat (2015). ‘De Valera: Long Fellow, Long Shadow’, p. 88

[17] Ibid, p. 94

[20] O'Malley, Ernie (2021). "On another man's wound: a personal history of Ireland's War of Independence", p. 325

[23] Barry, Tom (2013). "Guerrilla days in Ireland", pp. 188-189

[24] Borgonovo, John (2013). "Separating fact from folklore", Irish Examiner

Comments

Post a Comment